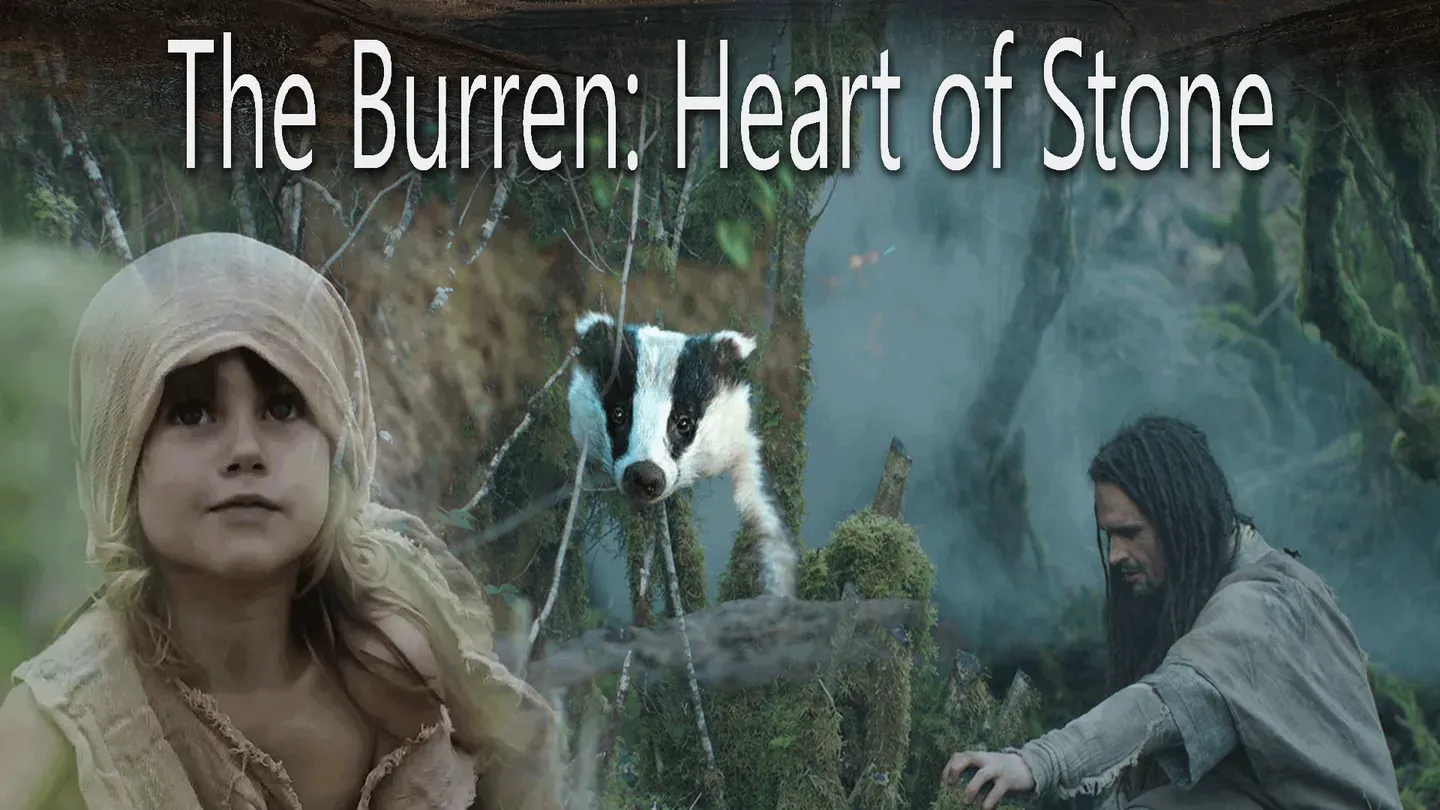

Song of our Ancestors

Episode 102 | 50m 52sVideo has Closed Captions

The two-part documentary series unveils the secrets hidden in the stones of the Burren.

In the countryside of County Clare, Ireland, is the Burren, a mysterious place unlike anywhere else, with deep caves, a stony landscape, and ancient dolmens, ring forts, and castles. The two-part documentary series The Burren: Heart of Stone, narrated by award-winning Irish actor Brendan Gleeson, unveils the secrets hidden in the stones of this dramatic wind-swept countryside.

The Burren: Heart of Stone is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Song of our Ancestors

Episode 102 | 50m 52sVideo has Closed Captions

In the countryside of County Clare, Ireland, is the Burren, a mysterious place unlike anywhere else, with deep caves, a stony landscape, and ancient dolmens, ring forts, and castles. The two-part documentary series The Burren: Heart of Stone, narrated by award-winning Irish actor Brendan Gleeson, unveils the secrets hidden in the stones of this dramatic wind-swept countryside.

How to Watch The Burren: Heart of Stone

The Burren: Heart of Stone is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship>> Funding for this series has been provided in part by the following.

♪ >> Whether traveling to Ireland for the first time or just longing to return, there's plenty more information available at Ireland.com.

♪ ♪ ♪ >> On the far west of Ireland is a place like no other.

Battered by Atlantic gales, sculpted into otherworldly shapes.

We call it the Burren, the "place of stone."

At first sight it's wild... timeless... empty.

Few landscapes on Earth present clues to our human past as vividly as the Burren, its structure providing both the raw materials with which we wrote our past, and a subterranean labyrinth preserving clues of how we once lived.

It's almost as if the Burren wants to tell us our own story, a rich narrative of triumph, survival, upheaval, and the human spirit.

♪ A story which is constantly reshaping how we think about human existence in Ireland.

And a story we continue to write.

♪ ♪ ♪ >> Attaboy.

Go on, go on.

Go back.

Come here.

[ Whistling ] ♪ We are here in the heart of the Burren.

It's a wonderful place to live and to farm.

The sights you see are incredible.

The sounds, the feelings.

[ Birds chirping ] It's a place that's both rich in archaeology and botany, and our own human story is rich and long here, and all around us we have evidence of that.

[ Sheep bleating ] I love that exchange between our own human story, the myth, and the landscape.

♪ To be out in those hills, maintaining that landscape, maintaining those walls, working with nature.

In a way, you're honoring the people who sweated it before you.

♪ There's an old magic in that.

>> One of the strangest things about the Burren is the walls.

Stretching from horizon to horizon.

An empty landscape crisscrossed by stone walls.

Follow these walls back in time, and they lead to another world.

♪ >> One of the things that makes the Burren truly remarkable as an archaeological landscape is the sheer density of sites.

As you walk across the fields you're literality tripping over the archaeology, dating back thousands of years right up to the recent present.

And its that that makes it different and exceptional amongst the archaeological landscapes of the world.

I've been living in and around and working on the Burren for the past 30 years, trying to really tease out the chronology of all this complicated archaeology that you can see on the ground.

And it all looks ancient, that sometimes it's difficult to actually figure out the differences in time depth.

♪ And we are talking about huge differences in time.

So when you see the tumbled-down old remains of cottages, they look ancient to us and in fact they are ancient.

They're at least a couple hundred years old.

But to the people, for instance, who built this fort, where we are now, Cahercommaun, this was built anywhere from 1,100 to 1,200 years ago, so this would have been, you know, ancient to the people that built those cottages.

This spectacular triple-ringed cashel is a residence.

It is a chiefly residence.

It had four round houses originally in it, so probably an extended family, possibly two or three generations living here, and most of the other area in this inner ring would have been open area, but open area for cooking, for storage, things like that.

♪ And even to the people that built this fort then, they built this under the shadow of a wedge tomb, just upslope from us.

That wedge tomb is a good 4,000 years old, so it would have been an incredibly ancient monument to the people that lived here in Cahercommaun.

And then if you go back even further, the people that built Poulnabrone 6,000 years ago, which makes it the oldest dated megalith in the entire island.

"Mega" just means "big," "lithic" is "stone."

These really are the legacy of the countless generations of people that lived here.

♪ To truly understand who you are not only as a person but who you are as a society, you really do need to understand where you came from.

♪ The Burren has the highest concentration of megalithic tombs in Europe.

It was once the epicenter of a great farming culture.

How and why did Stone Age people build these structures?

And why invest that much energy in farming on this bare rock?

♪ When this tomb was built, it was surrounded by a great forest, inhabited by a completely different ethnic group of Irish people.

♪ ♪ >> To really understand this landscape, we have to go back a lot, lot further, past the people that were building dolmens and walls and cairns and tombs and things.

We need to go way, way, way, way, way back.

If we go back before the Ice Age, 40,000 years, this landscape would have been totally different altogether.

All the mountains of the Burren would have been so much higher.

They're just stumps now of their former selves, they would have been a massive amount higher than it is today.

It's hard to imagine glaciers gradually moving further and further and further south.

So over millennia, ice will slowly grind down, it will literally bulldoze everything that's in its path out of the way, removing a kilometer thickness of rock off the top of this landscape.

♪ It is hard to imagine now, but it did happen, and it would have been really quite spectacular.

After the ice had scoured the land, we would have been left with a landscape reminiscent, really, of perhaps Greenland or Iceland.

♪ Then gradually over thousands of years, plants started to come in.

♪ And it didn't take very long before a completely new landscape began to emerge.

The landscape would have turned into this incredible forest.

♪ ♪ What an amazing environment that must have been, absolutely teeming with life.

♪ ♪ Imagine there were no humans at all here, so the wildlife would have been just incredible.

♪ This woodland continued to flourish for thousands and thousands of years.

But now all that's really left of that original forest is probably where I'm standing.

♪ Probably our most beautiful native tree, the Scots pine, the last remnant of that mixed forest with pines and birch and oaks and hazel, ash, and various other trees in it.

♪ >> As the forest matured and expanded, new inhabitants appeared.

♪ >> There have been three quite genetically distinct populations living on the island, and in the Burren, at different points in time.

These three populations of Irelanders correspond to very clear cultural periods.

The Burren is amazing because it's sort of a stage where we can watch these different populations meet and mingle with each other over time and how that all plays out.

We've been using tools that were actually developed in forensics to try to build up a database of ancient Irish human genomes from all periods of the island's prehistory to understand how the modern Irish gene pool came about.

A genome is an entire map of your ancestry and all of the populations who came before you, so every genome we get gives us a piece of new information about the history of, not just the Burren, but of the whole island.

With ancient genomes, we get to predict how ancient people looked, what diseases they might have been susceptible to, we can look at what pigmentation profiles they had.

There's been some really surprising results.

The Irish hunter-gatherer population don't have any of the mutations associated with light skin.

We predict that they actually had quite dark to black skin.

♪ But what we also find in Irish hunter-gatherer genomes is a suite of mutations that are associated with blue eye color.

These individuals might have had quite a striking pigmentation profile that we don't really see today, dark skin with the bright blue eyes.

♪ ♪ >> We have evidence for hunter-gatherers on the coast of the Burren around 9,000, 10,000 years ago.

What we have are small sites, so, little dumps of shellfish.

And these would have been small bands of fairly mobile hunter-gatherers that moved around the landscape, hunting, fishing.

We would imagine that they probably trekked inland for various resources -- hazelnuts, hunting wild boar, something like that.

But these earlier hunter-gatherers didn't leave much of an impact on the landscape.

[ Birds chirping ] ♪ >> We can only imagine how these hunter-gatherers lived.

Undoubtedly they would have had a deep understanding of their environment and been skilled at using the resources with which they were presented.

♪ The Burren is a huge repository of ancient burial places and human remains.

Because the limestone is particularly good in preserving bone, we can look at what impact, if any, the dark-skinned and blue-eyed hunter-gatherer has had on the Irish gene pool.

>> So, we had this Irish hunter-gatherer population living, it seems, relatively undisturbed on the island for about four millennia.

And then everything changes.

Agriculture happens, farming, and it happens fast.

The earliest evidence we have of early farmers in Ireland is in the Burren.

[ Woman vocalizing ] ♪ This is the Neolithic period, the new Stone Age, 6,000 years ago.

And we know now, from ancient genomes, that farming was accompanied by a whole new group of people moving into the continent from the region we now know as modern-day Turkey.

♪ They brought domesticates to the island -- cattle, sheep and goats.

Pottery, new housing structures.

♪ They have lighter skin than our European hunter-gatherers, it seems, but still sallow and typically dark eyes and dark hair.

I think it's quite hard to imagine what it must have been like to live in the Burren at that time.

♪ The question we had is, well, how did they interact with the Irish hunter-gatherer population?

Loads of new peoples arriving, it was probably quite exciting, maybe a bit scary.

There could have been violence.

This would have been quite a dramatic colonization event.

[ Bird screeches ] ♪ [ Birds chirping ] >> When the first farmers arrive about 6,000 years ago, seemingly one of the first things they do is they started clearing the trees.

♪ And they've got polished stone axes, so, you know, cutting down a primeval forest covering is a huge undertaking.

♪ ♪ ♪ If you're clearing your fields it might be much easier to go into these areas with thin, rocky soils and then clear them, so that may well be one of the reasons why we have Poulnabrone located where it is on the Burren.

♪ ♪ The picking up of stones and putting one stone on top of another to build a wall, to keep their animals in, dividing off the landscape, this is something that never happened before the first farmers.

♪ ♪ The clearance of forests would have been a huge thing to the hunter-gatherers that were here previously.

And ritually, what the first farmers do, is they start building big megalithic tombs.

♪ As we stand now, Poulnabrone is currently the oldest dated megalith in the entire island.

So that's remarkable in and of itself.

The question arises, why did people build big tombs like this, big tombs out of big slabs?

You can see these slabs are absolutely massive.

They weigh many tons.

Now, these would have had many meanings to the people, but certainly one of the meanings they seem to have held is taking ownership of the land.

One way that we, you know, try to understand how things like megalithic tombs were built is we use anthropological studies, studies of living people or in the recent past that built megaliths.

And what we know, one commonality that comes out of these studies, is that they're built by large community work parties.

It's a huge kind of communal party event when something like this is built.

So when we look at Poulnabrone, which was built about 6,000 years ago, that's the sort of scene that we should have in mind -- you know, large groups of people gathered together here in this field, decorations, feasting.

The centerpiece of this whole thing would have been the construction of this tomb, and probably the crowning moment of that would have been dragging this massive capstone up on top of the tomb.

So it would have been a big event because the person or the family sponsoring the construction of this wants to get as much social capital out of it as they can.

They want people for generations to come, when they walk by this tomb, to recount the story of what a spectacle it was when it was built.

So all these ways of marking out the land, of claiming the land, this is something that we see with the advent of farming.

And that really then starts this interplay between the landscape and the people.

♪ ♪ >> What happened to the Irish hunter-gatherers, and how did this massive migration with farming play out?

We actually do have some evidence that there was admixture and interactions between the two very different groups, and that evidence actually comes from the Burren.

We are sitting right by Parknabinnia court tomb, which was built about 5,500 years ago by early farmers who came and set up a whole community society here in the Burren.

What makes this tomb so special is that we found a male individual interred within it, who's genome told us that he had an Irish hunter-gatherer in his recent family tree as recent as great-grandparent or great-great-grandparent.

So, what this genome really is, it's a snapshot of interaction between the indigenous hunter-gatherer communities in the Burren and the incoming farming populations.

[ Woman vocalizing ] ♪ There's no reason to assume that the moment the first farmers arrived, the indigenous hunter-gatherer population just disappeared.

They probably lived alongside each other for a while.

We can't say if it was peaceful, if it was violent, if it differed from region to region, but what we do know, at least in the Burren, is that some Irish hunter-gatherers contributed to an early farming society.

♪ We don't see much evidence of the hunter-gatherer tools within Neolithic contexts, so on a cultural level we don't see the input, which is why it's amazing to be able to see it on the genetic level.

♪ The Irish hunter-gatherer population, they're really a population shrouded in mystery.

We have no evidence that they contributed to the modern Irish population.

It seems that whatever little they contributed to the farming population was diluted beyond detection.

♪ ♪ At the start of Bronze Age, 4,000 years ago, we have another big influx of people coming in.

They are sort of the tail end of a large-scale migration that started up about a millennia beforehand in the Steppe region of Russia.

It's really only at that point in time that we see the establishment of the modern Irish gene pool as we understand it today.

♪ ♪ ♪ >> Farmers invest so much effort and labor into marking the land.

Certainly that's one aspect of these great megalithic tombs, like permanent symbols of territoriality.

[ Birds chirping ] And certainly of course, various rituals would have taken place in and around wedge tombs.

They are mortuary monuments, so they have the bones of men, women, and children in there.

They are in many ways containers of the dead.

They are wedges that are opened wider and higher to the southwest, and the point of that is that they are pointing to the southwestern horizon, to the land of the setting sun.

♪ But particularly where the sun sets in the colder, darker, winter months of the year.

In later Irish mythology, the southwestern horizon had links to the land of the dead.

♪ And then if we move even more recently, we have traditions like Halloween and Samhain, when again it's those darker autumnal evenings that are associated with the land of the dead.

These traditions that we still keep up today may have their roots going right back thousands of years all the way to the time of the wedge tombs.

♪ That really then starts this interplay between the landscape and the people, because those monuments that were built 6,000 years ago are still in the landscape.

They meant something to the people that built them, but then we see even later ritual uses of them, and of course then later folklore is laid on top of that and they continue to shape perceptions.

♪ ♪ >> I was always attracted to this place.

It's an old landscape, there's forts, there's burial sites, there's myth of the Tuatha Dé Danann, of the Glas Ghaibhleann, the fairy cow.

♪ They're older than the pyramids of Egypt, these old cairns.

People chose to be buried in this most incredible place, where you can see for miles and miles and miles.

That whole valley unfolds in front of you.

Were they in search too of something greater and beyond their own existence?

♪ After spending a day up here, walking or building walls, when you come off it, there's a huge vulnerability that strikes you.

You're carrying on the song of the ancestors.

♪ ♪ I often felt like when you're up here in these forts, there's no limit to your imagination.

Out there like -- they can be just out there, just out beyond that thin veil, that they are there still going doing their daily chores, like.

There's a world of vibrancy and singing.

It's a wonderful experience to be part of it, to be part of the great symphony of life.

♪ ♪ >> When we look at the Burren, you know, it has been farmed now for 6,000 years roughly.

As best we can tell, around the time 4,000 years ago and going slightly later, most people had lived in scattered farms.

The houses that they actually lived in don't seem to have been that substantial, so probably wooden round houses with a thatched roof.

Then what happens is the climate turns colder and wetter, and interestingly when it gets colder and wetter, the Burren gets used more.

And the reason for that would be because of the heat-retaining properties of the limestone and the thin soils, that it becomes even more valuable during climate downturns, that what you're getting is an increased use of the Burren.

♪ We seem to see a thriving of the Burren.

Because populations are increasing, people start coalescing into more core territories and building fortified hill forts.

♪ ♪ So by about 3,000 years ago, contemporary with the climate downturn, we have large areas of the Burren cleared, and we see the real proliferation of farming.

It's the period when we can see the most tree clearance on the Burren.

♪ >> Over thousands of years, farmers relentlessly cleared the forests.

They needed more agricultural space, so they kept clearing and clearing and clearing until we reached the point really where there was hardly any of the original forest left.

This of course, was a disaster for the soil, and combined with a change in climate, which saw a very much wetter and very much windier climate, this led to an environmental disaster on a colossal scale, because over a very short space of time we have massive soil erosion, which pretty much left us with the landscape that we had at the end of the last Ice Age.

Literally just bare rock.

The soil was washed away.

♪ ♪ >> The inhabitants of the Burren must have felt that the forces responsible for fertility had deserted them.

♪ Their dreams of a new land being washed away.

In response to this natural upheaval, it appears they turned increasingly to the supernatural.

>> If we look at the caves in the Burren, they are very, very rich in archaeology towards the late Bronze Age, so about 2,500 years ago to 3,000 years ago.

And at this time, regular farming life in the Burren becomes more difficult.

We don't see them constructing monuments or constructing burial cairns above ground at this time.

So we're seeing this movement from above ground to below ground, almost as a reaction to the climatic downturn.

People saw caves as very, very powerful and very potent places in the landscape.

It was a sacred domain, and there were only certain ritual practitioners who were going into them, so that the general population can see somebody walking up the mountain and they literally disappear.

♪ They're bringing all these gifts and leaving them in the deepest and the darkest part of the cave.

We have a whole series of newborn piglets and newborn lambs and newborn calves.

♪ We found this amazing little wolf tooth that had been perforated and would have been worn as a pendant.

We have a whole series of amber beads there, and those amber beads would originally have come from the Baltic.

They seem to have been leaving all of these high-status offerings presumably in the hope that they would get something in return.

I think the darkness is fundamental to all of this.

It's the darkness that they're looking for and the serenity and quietness and this remove from everyday life -- to go into these places and spend time there and commune with whatever they thought was in there, whether that was a spirit world or even just to get enlightenment and come out with new wisdom or new knowledge that the rest of the community didn't have.

And I think that's part of the appeal of archaeology, certainly with prehistory You get some very tantalizing evidence, but it's only a very small part of the picture.

It's never the full story.

>> It would appear this climatic downturn wiped out thousands of people.

Small resilient populations managed to survive in pockets, carrying forth the genetic signature of the Bronze Age people.

But for the next 500 years, the Burren is effectively abandoned.

And although the great forest with bears never returns, the landscape is once again covered in hazel and pine.

The tombs and caves have preserved bones and artifacts which give us insights into the lives of prehistoric people.

But dramatic new evidence has emerged suggesting that there was a human presence in Ireland long before the hunter-gatherers of 10,000 years ago.

The evidence of this doesn't come from the bones of people, but from the bones of animals.

♪ >> This bone, it just changed Irish human history and presence on our little island forever.

It just blows northwestern Europe open in terms of human movement, migration.

It changes everything.

♪ >> We have followed the story of people in the Burren for a period of 10,000 years, believing that the first people coming into Ireland came when the climate warmed after the last Ice Age.

But dramatic new evidence has emerged, suggesting that there was a human presence in Ireland long before the hunter-gatherers of 10,000 years ago.

>> The way I look at bones, they're treasure troves of information, that if I listen really carefully, they'll tell me their little secrets, and it's the secrets of their lives and how they lived and where they were from, and then how they died.

Limestone caves are great for preservation of bones themselves and also ancient DNA.

I've probably examined at least 50,000 bones -- and bone fragments because they're generally bone fragments rather than whole bones, so it's like looking at a jigsaw puzzle, but you don't know what the end picture is going to be.

By identifying the animal species from the bones, and how they lived and how they died, I can build up a picture of actually what was in the area at a certain time.

And in the Burren then we definitely had hare, Irish hare, red fox.

Was wolves as well.

We definitely had brown bear.

I think what would be very much impressive in terms of size and actual, I suppose, physical presence, would have been the woolly mammoth and the giant deer.

On another hand, though, to see herds of reindeer would have been, like, spectacular as well.

However, with new research, that's not the end of the story.

We actually have butchered reindeer bones.

We have two bottom bits of the femur, so the main hind leg bone, which actually have very deep chopping, almost like a chopping mark made by a broad flat tool, a flint tool or a stone tool.

And then also we have a fine cut mark on the vertebrae just behind the skull, so almost like it was associated with dismembering the animal in terms of removing its head.

So therefore we have to ask then, when did that animal die, what's the age of the bone?

And that's why we took a section of the bone and then we got it radiocarbon-dated.

And then we found a surprise.

♪ The radiocarbon dates came back, and I actually didn't tell my colleagues for two weeks because I was shocked, to say the least.

We had three separate dates -- 18,000 years ago, 25,500, and again at around 33,000 years ago, which is unbelievable.

♪ ♪ ♪ Like, this bone, it just changed Irish human history.

We have humans coming into Ireland 33,000 years ago, which changes everything for Ireland and changes actually northwestern Europe as a whole.

Because they're following their prey species.

It's what they eat from but also what clothes them and creates shelters.

♪ >> The true nature of these nomadic hunters is still a mystery.

The world which they inhabited had no boundaries.

We continue to learn about our human past from this restless landscape.

For millions of years the Burren has accumulated clues for us to interpret.

Stories emerge from the black depths of the past into the light of the present.

These stones can speak because an ear is there to listen.

We have witnessed the ebb and flow of human populations in the Burren.

Cultures fade and new ones emerge.

For thousands of years, humans have played a fundamental role in shaping the Burren.

We are now at a unique point.

We are in the position to combine the perspective of history with the foresight and knowledge to inform how we influence this landscape for the future.

>> I love natural landscapes and to being close to nature and surrounded by nature as it should be, not as we have left it over thousands of years of land use.

>> Farmers enhance the landscape.

Their presence brings so much to the landscape.

When the farmers, as they did traditionally, skin these fields in wintertime without damaging them or poaching them, that's when they get enough light and enough space for the small Burren flora to emerge and to thrive the following year.

The presence of all these beautiful flowers, that really lovely species-rich grasslands, full of orchids and gentians, and mountain avens in summertime, that relates a lot to unique farming activities.

Farming itself isn't really viable, and if you're farming here you're probably losing money.

It's a very unforgiving landscape and a very unforgiving climate.

That's not a fun lifestyle for a lot of young people, especially today, but that's really what it takes.

If you didn't graze these grasslands in wintertime, if you grazed them in summertime, you'll lose a lot of your flora, and eventually it'll lead to maybe bracken and bramble and scrub encroachment.

We can see whole farms that have kind of largely disappeared now from hazel encroachment.

We encourage the farmers to take it out, but it's a difficult job.

I'd really worry that we'll lose a lot of our farmers, and when we lose that, we lose a lot of the traditions, we lose a lot of the knowledge, we lose the connection with the place, and we do lose a lot of our biodiversity.

♪ >> We hear so much about biodiversity, which is good, but a lot of what we consider as biodiversity is a result of man's influence on the landscape.

If you're left with acres and acres and acres of hazel woodland, your biodiversity goes right down, but that is the original landscape.

The hazel woodland is absolutely what was here and it is completely natural.

I have no problem with allowing the land that isn't perhaps being used to revert to pretty much do its own thing.

It would only take a few years before the hazel scrub would eventually turn into hazel woodland.

This would eventually bring in other species.

Many thousands of years ago the range of species in these woodlands would have been considerably more than it is at the moment, and presumably in time those species would gradually find their way back in here once again.

Until recently, people that lived and worked in the Burren really had no knowledge of the impact of their actions on the landscape.

That's completely different now.

We have knowledge, we have information, and we have choice, so really it is up to us now to choose and make the right decisions on how we look after this landscape for the future generations.

>> The Burren isn't a wilderness.

It's not a natural landscape.

It's a lived-in cultural landscape.

It's been managed for thousands of years, and that management through farming has shaped this incredible cultural heritage.

Combined with that we have this wonderful biodiversity and geological fascination, so it's an incredible landscape, I think it's a place of, for me, inspiration.

Every time I take a walk in the Burren, I see something new or I learn something new or I'm inspired in some different way.

♪ We don't want to come along in 20, 30 years, not having intervened and having lost so much of the Burren.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> I always felt like that up in those hills I have seen sights, that I've seen times and places that I wish I could show the world.

[ Bird screeching ] ♪ Mountains, sky, and stone opens its wings.

[ Birds calling ] ♪ So it's an old place, it's an old landscape.

And I always felt there was an echoing, an echoing coming to us, an echoing coming to this generation.

Remember, we are echoing too.

What we do and what we say, we are echoing too to some other generation.

♪ Everybody needs those hills, maybe just to be quiet, walk alone, and let it flow to you.

And it will flow to you, and if you open your heart to landscape, you know, it is the great teacher.

Landscape and nature is the great school.

There is no doubt about that.

That is the great school.

♪ ♪ [ Geese honking ] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Funding for this series has been provided in part by the following.

♪ >> Whether traveling to Ireland for the first time or just longing to return, there's plenty more information available at Ireland.com.

♪

The Burren: Heart of Stone is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television